|

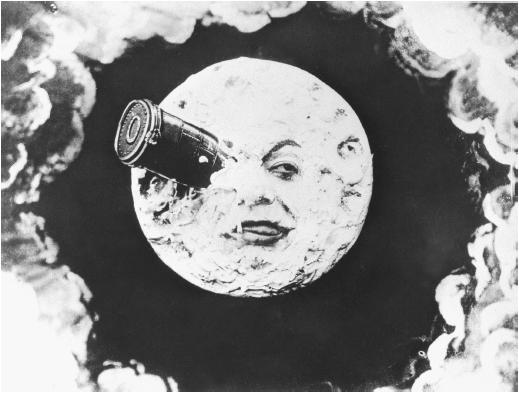

| Image from The Cabinet of Dr Caligari (1920) Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons |

Why would I do that? I know some might say that film and literature are separate disciplines and naturally have different requirements (for example, an establishing shot is essentially in film, but if a writer takes too long to ’set the scene’, it can make for very dull reading) but I’d argue that writers can still learn new things from different sources. Writers shouldn’t fall into the trap of assuming that only studying writing can help their work. I’m not saying that you should cut all dialogue from your work, but let’s have a look at the bigger picture…

1) Show, Don’t Tell

This is probably the king of all silent cinema techniques that the writer should use, and is arguably advice you’ve heard before. Without dialogue, the actors have to display every emotion either on their face, or through their body language. It is indeed true that a picture tells a thousand words, and we don’t need reams of exposition when faced with a faltering smile or a pouting femme fatale with her arms tightly folded across her chest. We don't need someone to tell us that Dr Caligari is a nutjob when he's depicted with a crazed stance, a wild facial expression and melodramatic gesticulations - we can see it for ourselves. Show us what’s going on with your characters, let their facial expressions and body language do the talking. We’re aware of it all the time in real life, so why not try it in your writing?

2) No Info Dumps!

It’s an attractive tendency of fiction to allow your characters to dole out back story through so-called ‘info dumps’, usually within lengthy passages of dialogue. The brevity of the silent film cue card doesn’t allow for masses of text, so key visuals are chosen instead to fill in the back story. Just as film fans were trusted to be able to understand the implications of specific shots, trust your readers to pick up on the small details and fill in the rest themselves. For example, you don’t need to waste paragraphs describing a character’s reliance on alcohol – just show them putting yet another empty bottle into a crate full of other empty bottles.

Do You Really Need Back Story?

If you’ve seen The Artist, you’ll realise that neither George Valentin nor Peppy Miller have in depth backstories. George is a successful silent film star and Peppy is a girl who comes to Hollywood looking for fame. We never learn much more than that, but nor do we need to. The performances and actions of both characters make it easy to like them and root for them, without time needing to be taken to explain how past events have coloured or shaped their present decision-making. Charlie Chaplin gave his Little Tramp very little backstory because the films were set in the 'here and now' - we didn't need to know what he did for a living before working in the factory in Modern Times because it's irrelevant. I know writers are counselled to know the entire biographies of their characters but you don’t have to communicate that to the reader – just pertinent details so we understand why they’re doing what they’re doing.

|

| Courtesy of The Hitchcock Project |

In 1926, Alfred Hitchcock directed Ivor Novello in The Lodger, a gripping thriller about a serial killer loose in London. One notable scene has Novello pacing back and forth in his room while the family with whom he is lodging listen in the room below, convinced he is the twisted killer. How on earth do you communicate the sound of someone pacing if you can’t hear it? You do what Hitchcock did and film Novello pacing on sheet glass, then superimpose it over the ceiling so it looks as though we can see through the ceiling to the room above. No sound required.

It is this inventive spirit that marks the silent filmmakers as true pioneers, and also a good source of inspiration for writers. Think about what you’re trying to communicate, and how you’re going to communicate it, and ask yourself… is there a more inventive way of doing so?

Check Your Pacing

Without dialogue to puncture the silence, early films couldn’t rely on lengthy speeches or conversations to pass the time. Films had to be short due to the technical capabilities of the equipment, but few viewers would sit through a film rife with pacing problems. D W Griffith’s Birth of a Nation ran at just over three hours long, but his tendency to focus on imagery for imagery’s sake left the film feeling tedious and self-indulgent. Writers can fall into the same trap, either by rattling off reams of purple prose, or by getting bogged down in dialogue and “witty” exchanges that soon become staid. A balance between the two should always be sought, and always ensure that your pacing remains even – try passing your work to a trusted reader, and if they find some passages too fast or slow, then double check to the balance between dialogue and prose.

Do you find that cinema principles can help enrich your writing?